Canadian insight: Making sense of Marshall McLuhan

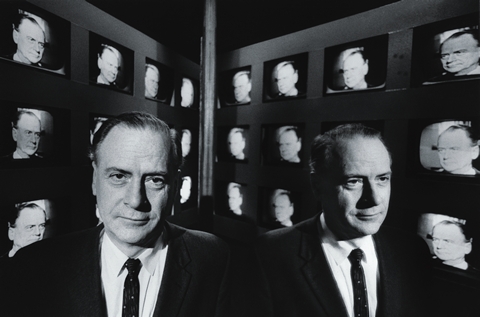

ItŌĆÖs inconspicuous, even humble, just about the size of a tall two-car garage off a parking lot, near the larger buildings that make up St. MichaelŌĆÖs College. On the summer day I visit, the diminutive coach house where Marshall McLuhan once worked has been temporarily cleared of most of its furniture and umpteen books. There is just a sole remaining intimation that McLuhan spent the last decade of his life working here (he took it over in 1968 and died in 1980): In the almost empty main room, thereŌĆÖs the chaise longue that the lanky man used to lie upon during his famous seminars, extemporizing fluently. By the accounts of people who knew him, he was one of the 20th centuryŌĆÖs great talkers.

Read also

Nearby, the bells toll at St. BasilŌĆÖs Church ŌĆō where McLuhan, a devout (but not dogmatic) Catholic went to mass every midday and where, in honour of his centenary (he would have turned 100 in July), a memorial mass was recently held for the family, friends and enthusiasts of the late media theorist.

On the walls of the coach house are photos of bygone technologies, ones that were cutting edge in McLuhanŌĆÖs day ŌĆō typewriters, Dictaphones, computers larger than 747s, which, despite their size, were less powerful than todayŌĆÖs laptops. These pictures, shot by photographer Robert Bean to honour McLuhanŌĆÖs centenary, emphasize the theoristŌĆÖs achievement in anticipating so much about the Internet. On a white screen, near the chaise longue, a slide-show depicts miscellaneous items from archives relating to McLuhan: the gaudy bands from the cigars he savoured; pages from a draft of one of his books typed by his wife with his edits scrawled all over them; a passport photo from when he was a fresh-faced youth from the prairies, about to embark on the international academic odyssey that would (eventually) bring him such acclaim.

I peer hard at this photo of a blandly handsome, long-headed young man, looking (in vain) for signs that heŌĆÖd become remarkable. ŌĆ£Marshall McLuhan, what are you doinŌĆÖ?ŌĆØ This was a catchphrase on Rowan & MartinŌĆÖs Laugh-In, the comedy show big in the late 1960s ŌĆō intended to poke gentle fun at the abstruse thinker. Certainly, McLuhan had been fab in that era. With the publication of Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man in 1964, heŌĆÖd captivated ŌĆō and puzzled ŌĆō a generation. Suddenly, he seemed to be everywhere, referenced on Laugh-In; interviewed by Playboy; giving talks to the top executives at GE, IBM and Bell Telephone. No less astute a cultural observer than Tom Wolfe compared him in the pages of New York magazine to revolutionary thinkers such as Freud, Newton and Darwin. The Sage of Aquarius, they called him. Another academic might have squirmed at the cutesy designation. With his own love of wordplay and disdain for the often stuffy, standing-on-ceremony of academic life, he probably loved it.

Lewis Lapham, the former editor of HarperŌĆÖs and current head of LaphamŌĆÖs Quarterly, says that McLuhan was no less than the foremost oracle of his age. ŌĆ£Seldom in living memory,ŌĆØ he comments, ŌĆ£has so obscure a scholar descended so abruptly from so remote a garret into the centre ring of the celebrity circus.ŌĆØ

McLuhan grew up in the ŌĆ£remote garretsŌĆØ of Edmonton and Winnipeg, the son of a sociable, seldom-do-well father and a striving and strident mother, who helped support the family by giving dramatic readings of the acknowledged literary greats across the prairies and sometimes beyond. After studying some of those sonorous greats himself at the University of Manitoba, McLuhan won a scholarship to continue his literary studies at Cambridge ŌĆō the reason for obtaining a passport photo.

At Cambridge, he learned to prefer the modernists ŌĆō James Joyce and T.S. Eliot, particularly ŌĆō to the grand figures of the Victorian and earlier eras. The modernists larded their technically difficult works with references to the new electric technologies ŌĆō telegraph, telephone, radio, motion pictures ŌĆō providing a model for engagement with technology that McLuhan himself would follow. He learned to analyze poetry and prose dispassionately ŌĆō the no-nos were to say how a work made you feel or to speak to its moral compass. He also closely examined combinations of words for their effects. This was, essentially, the same close-reading, ostensibly judgment-free, effects-based approach heŌĆÖd later take to parsing newer media.

He began to shift gears from literary criticism to media analysis during his first teaching job at the University of Wisconsin ŌĆō Madison. ŌĆ£I was confronted with young Americans I was incapable of understanding,ŌĆØ he was quoted saying in Playboy. ŌĆ£I felt an urgent need to study their popular culture in order to get through.ŌĆØ

And so, in his first book, The Mechanical Bride: Folklore of Industrial Man, he applied his literary-critic tools to magazine advertising and comic strips. His book, a series of essays, came out in 1951, five years after heŌĆÖd come to the University of Toronto as a junior English professor at St. MichaelŌĆÖs College. It was idiosyncratic enough to dismay some of his new colleagues ŌĆō pop-culture criticism was not yet a wholly respectable pursuit for an academic ŌĆō and it also didnŌĆÖt make much of a splash beyond the academy.

The Mechanical Bride lacked the intellectual framework that would distinguish his later works, but the bookŌĆÖs scattershot brilliance did impress a man who would become McLuhanŌĆÖs key intellectual model: U of T economic historian Harold Innis, who had made his reputation by analyzing Canadian history through the lens of the staples it exported. The admiration was returned: McLuhan would emulate InnisŌĆÖs so-called ŌĆ£mosaicŌĆØ writing style (aphoristic, dense, not linear) and appreciated the substance of the older manŌĆÖs thought. He found particularly intriguing InnisŌĆÖs theory that different types of media each had a ŌĆ£biasŌĆØ ŌłÆ a tendency toward different political and social messages. This would presage McLuhanŌĆÖs more radical dictum that made the medium itself the message.

McLuhanŌĆÖs thoughts also gained solidity and momentum through an innovative collaboration with U of T colleagues from different disciplines, including anthropology, psychology, urban planning and economics. With a generous grant from the Ford Foundation to study the shifting media environment in the early days of the television era, McLuhan and his colleagues conducted research, held seminars and wrote up their thoughts in an academic magazine called Explorations, which was published at U of T. Typical was an experiment that had different students absorbing the same lecture by print, television and radio, and then being tested on their retention. TV won, radio came second and print brought up the rear. ŌĆ£In these seminars,ŌĆØ says Janine Marchessault, a York professor and McLuhan scholar, ŌĆ£it was really a think-tank environment, everyone trying to figure out, in McLuhanŌĆÖs words, what the hell was going on.ŌĆØ

Read more?

Internet site reference: http://www.magazine.utoronto.ca/feature/marshall-mcluhan-centenary/

Comments

There are 0 comments on this post