Self-Publishing: The Good, the Bad and the Even Worse

Only a few years ago, self-publishing printed books through Publish on Demand (POD) publishers was becoming very popular. It represented a big step forward in what was then still known as “vanity press” – authors who could not or would not secure publishing deals with “real” publishers could instead print their work on their own terms for a fee. Where once vanity publishing meant paying rather large fees for a crate of books you then sold out of your garage or the trunk of your car, the rise of POD technology made self-publishing both more respectable and more cost-effective. For a much smaller fee (compared to printing in quantity) to set up the book (and possibly a hosting fee to keep it live), any author could have a paperback or even a hardcover from whose sales he would derive small royalties. Such authors then sat around at card tables at their local bookstores or public libraries, desperately trying to make eye contact with nonplussed shoppers.

The market continues to evolve. Now that e-books have eclipsed printed books, barriers to entry for new authors are the lowest they’ve ever been. A prospective author no longer needs to set up a printed book with a POD publishing house. He or she can now go directly to Amazon, reaching the pool of prospective readers the massive online bookseller serves. Amazon’s direct publishing program, wherein the company offers Kindle-platform e-books (and even printed paper books through its company CreateSpace), has proven immensely popular. Self-publishing promises authors more control, faster time to market, global distribution and higher royalties.

Of course, self-publishing also allows authors who could not otherwise secure a publishing agreement to bring their books to market on their own terms, which is largely the point. For every successful author formerly published by the Big Five, there are thousands of aspiring (and often incompetent) would-be writers pumping illiterate crap onto Amazon’s pages. Their e-books, many of which are offered for free, are the distilled essence of aspiring amateur writers. They just want someone to read their work. Some show promise; many do not. It falls to the customer to wade through the dizzying array of offerings in an effort to dig up a decent read.

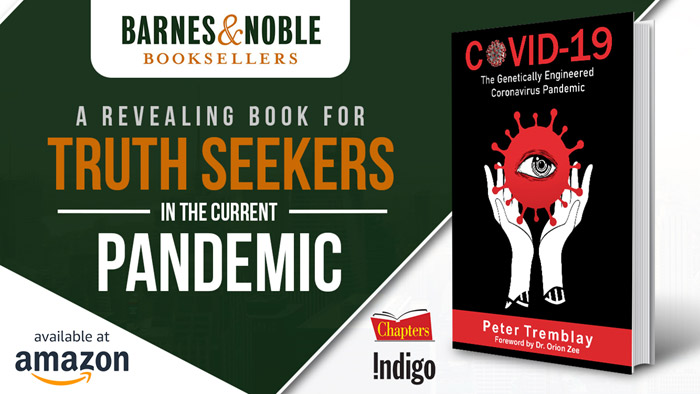

There are other issues associated with self-publishing that might not be apparent immediately. One is that authors who publish their own work may be printing plagiarism or libel. The typical self-publisher cannot possibly screen the avalanche of badly written garbage that crosses its virtual desks, so these companies rely on reporting after the fact to alert them of questionable content. They’ll err on the side of caution so as not to become party to any lawsuits that result, but the book, complete with ISBN number, now exists, and will exist forever even if it is not readily available.

Self-publishing house iUniverse offers the following advice to would-be authors on its website: “[I]t is your responsibility to ensure that your manuscript is free from libelous statements or content and that you have not violated the privacy rights of another person or party.” In other words, you, as the author, are on your own. There are no gatekeepers to protect you from yourself.

Henry Mance, writing for Financial Times, explains that this “new era of self-publishing” is not without its critics. “Self-publishing, once seen as an exercise in vanity, has become a viable economic enterprise for authors of e-books,” Mance asserts. “Nearly 460,000 titles were self-published globally in 2013, up fivefold in five years. … The industry is ‘evolving from a frantic, wild west-style space to a more serious business,'” according to one research group. … [E]very part of the publishing process can now be replicated by authors themselves. … Self-published works account for 50 percent of author royalties generated by e-books on Amazon. … By contrast, the Big Five publishers deliver 35 percent of e-book royalties.”

Mance goes on to quote business competitors who claim Amazon is using its self-publishing platform to “bludgeon” publishers by reducing their profitability. Barnes and Noble, meanwhile – one of the few brick-and-mortar chains still a going concern in today’s challenging publishing landscape – still steadfastly refuses to stock print books published by Amazon. If you’re a self-published author and you publish through Amazon, in other words, you won’t be seeing your work on bookstore shelves any time soon, at least not in a Barnes and Noble. This is less of a problem for obscure, beginning authors than for well-known and established ones, who stand to lose a significant portion of their market if they switch from the Big Five to a self-publishing platform in order to reap more of the profits of their own sales.

Where does this leave authors and their audiences? The answers are unclear as the market continues to change. There are good self-published books. There are also many bad ones. As gatekeepers to the world of publishing continue to vanish, writers and readers alike will be forced to navigate uncharted waters. Their shared goal – finding something decent to read – is both easier and harder thanks to the evolving technology that makes it possible.

Media wishing to interview Phil Elmore, please contact media@wnd.com

Comments

There are 0 comments on this post