Going for the Green at the Pan Am Games

Constructing unique world-class competition facilities for multisport events often leaves behind overbuilt, expensive and underused relics. With this harsh reality in mind, organizers for this summer’s Pan Am and Parapan Am Games in Toronto are taking lessons from other host cities to develop best practices for infrastructure design and construction during both competition and post-games operation. Placing long-term legacy ahead of short-term spectator demands, planners are prioritizing venue usability after the games in an effort to produce one of the most sustainable multisport events in the world.

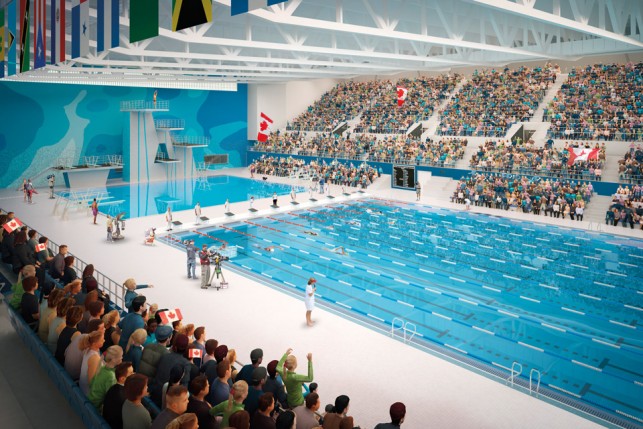

While Toronto 2015 will use 15 renovated and rehabilitated venues, construction of new facilities is part of most major multisport competitions. The CIBC Pan Am/Parapan Am Aquatics Centre and Field House is the largest single construction project for the 2015 games – and its $205-million price tag is also the largest single investment to date in Canadian amateur sport. Yet the complex, located on the University of Toronto Scarborough Campus, is designed for long-term sustainability, both in construction and operation.

Architect’s rendering of the CIBC Pan Am/Parapan Am Aquatics Centre and Field House exterior.

A geothermal system of 100 boreholes, each reaching 200 metres deep will provide approximately 40 percent of peak building cooling needs, and 20 to 50 percent of the peak-heating load.

But design teams have been successful in using building methods and technologies that count as credits toward LEED certification, an international rating system for green buildings and neighbourhoods. For example, the entire 312,000-square-foot facility includes a geothermal system of 100 boreholes, each reaching 200 metres deep. This system will provide approximately 40 percent of peak building cooling needs, and 20 to 50 percent of the peak-heating load. The roof of the Aquatics Centre boasts a solar array to help offset energy costs. That system is expected to produce 690,000 kilowatt hours annually, approximately 6.5 percent of the total energy needs for the facility. Through such features, designers have achieved LEED Gold certification (the second-highest LEED ranking) for the Aquatics Centre and Field House.

To work toward the Toronto Green Standard, which aims to reduce the city’s greenhouse gas emissions beyond the criteria laid out by the Ontario Building Code, the complex also incorporates a green roof over the training pool and other sections of the facility. The venue has automated systems for ventilation, heating and cooling; detailed monitoring to compare these systems’ performance against benchmarks; and water-saving and water-recovery systems.

To accommodate future sporting events and community needs, the Aquatics Centre portion of the facility will be scaled down following Pan Am competition. Much like the aquatics centre built for the London 2012 Olympic Games, the Toronto facility will reduce capacity from approximately 10,000 to 3,200 seats – still enough space to host other world-class competitions. Temporary external walls will be removed once the seating is reduced and a permanent exterior wall will be installed, leaving more outdoor space for community pick-up and drop-off.

If venues exist primarily for the development of high-performance sport, the local community gains little more than upkeep costs

Such concerns for “legacy” are increasingly driving venue design for Olympic and Pan Am competitions. Decades ago, legacy referred to how facilities would support the development of future high-performance athletes. The quarter-century-old bobsleigh track in Calgary, for example, has contributed to strong performances by Canadians at more recent Olympic and World Cup events. However, such venues are expensive, and if they exist primarily for the development of high-performance sport, the local community gains little more than upkeep costs.

In contrast, the Richmond Oval, used for speed skating events at the Vancouver 2010 Olympic Games, has been converted for use as a community recreation and fitness centre. The speed skating track was removed and replaced by basketball and badminton courts, hockey rinks and gym space. The legacy plan was aimed squarely at encouraging the public to enjoy an active lifestyle.

The 2015 Pan Am Velodrome, built to LEED silver specifications in Milton, Ontario, blends the models used in Calgary and Richmond. The banked track will host cycling competitions at the games, then will be maintained over the long term as a training facility for elite athletes and neophytes alike. The infield of the track – a marshalling area for athletes and coaches during the games – will be converted to three basketball courts. A gym and other fitness facilities will also be available to the general public, supported by “learn to ride” programs aimed at getting more people to try track cycling. The Velodrome will thereby bolster recreation opportunities in one of the fastest-growing parts of the Greater Toronto Area (GTA).

Canada’s track cycling team will also benefit from the Pan Am Velodrome: The team currently trains in Los Angeles because an appropriate venue previously did not exist in Canada. Both Cycling Canada and the Ontario Cycling Association are setting up offices in the Velodrome.

Not all venues designed for the Toronto Pan Am games will remain beyond the summer of 2015. Many of the competition and festival venues around the GTA fall into a category of facilities known as “overlay.” Plans for overlay projects entail renting and constructing temporary grandstands, tents and other facilities as needed, then removing them once the event is over. Such temporary venues will be erected around the GTA, including at Nathan Philips Square in front of Toronto City Hall. The building process for overlay features started this spring and will take approximately six weeks. Once the games are finished, the equipment will be disassembled and returned to the stage and equipment rental companies.

Like the seating reduction plan at the Aquatics Centre, every Pan Am venue has some facet of overlay construction. The Direct Energy Centre, currently a convention venue on the grounds of the Canadian National Exhibition, is being converted into competition areas for a variety of sports, including squash, racquetball, basketball and handball.

The CIBC Pan Am/Parapan Am Park on Toronto’s waterfront, pictured at night.

“For Toronto 2015, our focus has been on what we need for the long term,” explains vice president of overlay John Baker. “Overlay fills in the gaps. The process in Toronto was really about figuring out our existing stock of venues. If there’s not a long-term need for a facility, the whole thing is done through overlay.”

The Pan Am beach volleyball facility, much like the venue for the 2012 London Olympics, is completely overlay. Only the sand will remain after competition is complete, and even that will be relocated to other facilities.

The CIBC Pan Am/Parapan Am Athlete’s Village

looking west toward downtown.

The games’ largest overlay projects will augment the Pan Am/Parapan Am Athlete’s Village. This LEED Gold project was constructed for the games on a 32-hectare site near the Toronto waterfront. While the village will provide housing for 10,000 athletes and coaches, some accommodation will also remain after the games: 787 units will be sold at market value; 253 units will be made available as affordable rental housing; and George Brown College will take over one building as a residence capable of housing 500 students. The overlay components include the main restaurant for athletes and coaches, a temporary facility with a kitchen capable of serving 2,500 people. A welcome centre and small shopping plaza will also be constructed entirely through overlay methods, including tents and hard-walled temporary structures.

“Toronto 2015 has set a high standard in terms of overlay use,” said Baker, who has worked on multisport events since the Sydney 2000 Olympic Games. “Other games have used less overlay or built only permanent facilities. We’ve really worked to try to avoid that white elephant in our planning.”

Beyond creating locations for events, Pan Am organizers are also tackling transportation. Navigating Toronto has become a sore point for many people in the GTA as car traffic has pushed average commute times to well over an hour. With more than 250,000 Pan Am spectators expected in Toronto this summer, getting around the city could become even harder. The Ontario Ministry of Transportation is finalizing an overall transportation plan for the games, part of which will rely on bike-share programs.

The largest such system is Bike Share Toronto, operated by the Toronto Parking Authority since it took ownership from Bixi in 2013. Although the system has changed hands, Bike Share Toronto is committed to its predecessors’ expansion plans. The existing system consists of 80 bike parking and pay stations and 1,000 bikes. Another 20 stations will be added ahead of the 2015 Games. These new stations will be distributed to align with major Pan Am venues, then redistributed after the games to expand the current Bike Share Toronto layout.

“Bike Share Toronto will also corral a fleet of additional bikes to handle demands that exceed the capacity of a standard station when games events finish,” says Marie Casista, vice president of real estate and development for the Toronto Parking Authority. “The most likely locations for those corrals will be at major venues like BMO Field, Union Station and the Rogers Centre.”

Bike Share Toronto is also considering investment in additional communications efforts to help explain the system to new users and visiting tourists. “We really think bike share is an excellent form of transportation, and a key part of the transportation system in Toronto, not just for the Pan Am games, but in general,” says Casista, adding that membership has increased in the last few months.

The Toronto 2015 Pan Am/Parapan Am Games will host elite athletes from across the Western hemisphere. Thanks to the efforts of planners and builders, venues that remain after the games will serve as legacy for swimmers, cyclists and the greater community in general, motivating Canadians young and old to embrace a more active lifestyle.

Comments

There are 0 comments on this post