Toronto: GTA sprawl goes out of control

Toronto’s downtown condo boom attracts a lot of attention, but the Toronto region is actually growing five times faster at its suburban edges. High suburban growth rates in Toronto and other Canadian cities are raising important future sustainability issues.

The good news for Canadian urbanism is that the Toronto and Vancouver regions are both showing significant population increases in active core neighbourhoods that are walkable, mixed-use and have access to transit. Unfortunately, as a report I recently co-authored shows, most other metropolitan regions did not show similar downtown growth from 2006 to 2011, and all regions are still experiencing a tidal wave of suburban expansion led by lower-density automobile-dependent developments.

Why is this a problem?

The huge growth imbalance between core neighbourhoods and automobile suburbs is not sustainable from economic, social or environmental perspectives. Perverse CitiesPamela Blais’ book Perverse Cities recently demonstrated the market distortions and flawed policy that subsidize our expensive suburban sprawl. She recommends better pricing and policy tools to reduce the economic incentives for sprawl.

The vast expansions of our automobile-dependent neighbourhoods have important social and health implications for those who are too young, too old or too poor to drive a car. There is a growing body of medical evidence that suburban lifestyles are correlated with higher obesity rates in children and adults. As for seniors, where will the coming wave of elderly baby boomers live after they lose their licences? Our public health doctors call for more walkable, compact and mixed-use neighbourhoods to meet our current needs and coming demographic shifts.

Environmentally, there is no question that extensive automobile use leads to substantially more greenhouse gas emissions compared to commuting by transit, walking or cycling. In addition, low-density suburban development requires more energy to heat and cool than more compact development. Toronto’s Regent Park redevelopment and Burnaby’s UniverCity are fine examples of more environmentally appropriate new communities, but we need many more examples across Canada to balance the rapid growth of our suburbs.

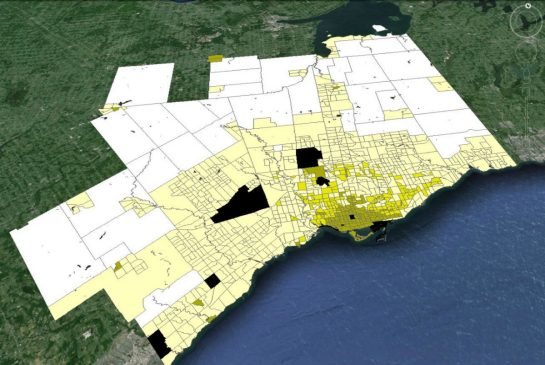

Our research analyzed this suburban growth by studying cities across the country using the latest census data. We found that Canada is still a suburban nation. More than two-thirds of the nation’s population (22.5 million) lived in some form of suburban neighbourhood in 2011. In the Toronto region shown in the map above, more than 86 per cent of the population live in a suburban neighbourhood.

Within every one of Canada’s 33 census metropolitan areas, the proportion of suburban residents is over 80 per cent. Many policy-makers underestimate the vast growth happening in the suburban edges. If we are going to have a more sustainable country, we have to figure out what to do about these suburbs.

Our report looked at three classifications of suburbs: exurbs, auto suburbs and transit suburbs. The exurbs (shown in white in the map above) are low-density rural areas where more than half the workers commute to the central core. Auto suburbs (shown in yellow) are districts where almost all the residents commute by automobile, including more than 4 million people or 72 per cent of the Toronto region’s population. Transit suburbs (gold) are neighbourhoods where a higher proportion of people commute by transit, home to 14 per cent of the region.

Only 11 per cent of the Toronto region’s population live in the active core neighbourhoods (shown in khaki), where a higher proportion of people commute to work as pedestrians or cyclists. Many of these core neighbourhoods were in downtown Toronto, but we also found them in the Beach and North York. A few towns such as Port Credit, Oakville and Newmarket also retained active cores after they were inundated by the suburban tsunami.

The population in Toronto’s core neighbourhoods grew by 52,000 people from 2006 to 2011, and the transit suburbs grew by another 26,000 people, which was good news. Meanwhile, the less sustainable exurban and automobile suburbs grew by 390,000 people, or 83 per cent of the regional growth.

Within the boundaries of the City of Toronto, more than two-thirds of the population growth was in the active cores and transit suburbs, but the districts outside the 416 area code saw another story. The outer part of the region was swamped by more than triple the population growth found in the city proper. And 99 per cent of that growth was in automobile suburbs and exurban areas.

Markham, Vaughan, Brampton and Mississauga are all making commendable efforts to create “city centres,” and their policies all say the right things about transit-oriented development and sustainability. But these worthy policies are being overwhelmed by the great influx of people into auto-dependent suburbs.

If suburban growth continues at these rates, Canada’s most important metropolitan region will suffer increased costs of sprawl, poor public health and a decline in environmental quality.

The inconvenient truth is that the Toronto megalopolis is getting more suburban every year. Our regional planning needs to reverse this trend and do a much better job of creating sustainable suburbs.

Read more...Comments

There are 0 comments on this post