10 Priorities Against the Conservative Punishment Agenda on Federally Sentenced Women

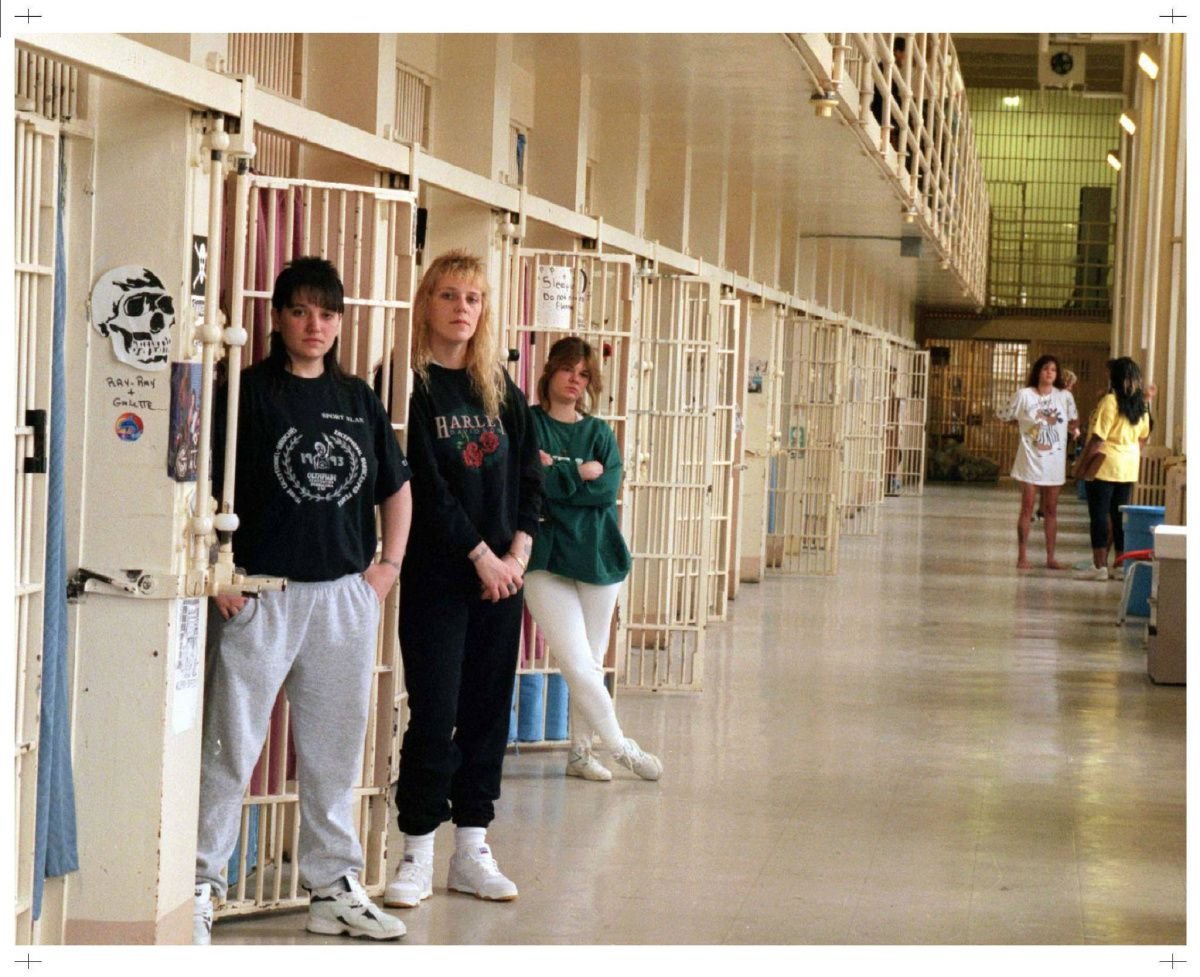

(JPP) - Life in a federal penitentiary is extremely challenging and tedious. We are removed from our friends, families and communities, and placed into a restrictive, oppressive environment. One of the primary purposes of prison is to rehabilitate and assist in our eventual reintegration into the community. However, once the Conservative government came into power under Prime Minister Stephan Harper, the focus of criminal justice laws, policies, and practices from 2006 to 2015 primarily became punishment. The following essay consists of a collection of observations and experiences from women incarcerated at Grand Valley Institution (GVI) in Kitchener, Ontario. The focus is on current policies and practices of Correctional Service Canada (CSC) that directly affect incarcerated women and our loved ones.

We identify ten key priorities for change based on our own observations, experiences, and through several meetings and discussions with fellow prisoners at GVI. These priorities are organized according to the following themes: justice, employment issues, programs and education, food and nutrition, visits and correspondence, reintegration and parole, media and communications, the focus on punishment, health and dental care, and mental health care. Within many of these categories are various sub-themes, which go into greater detail. Each section provides an overview of our experiences and observations. We then highlight some of the negative impacts on women at GVI because of these punitive policies and practices. Since so many negative impacts overlap, we return to these intersections towards the end of the paper. Finally, we suggest some recommendations in terms of priorities for change.

Priorities of Change

1 - Justice

The lack of justice is the largest category and the number one priority for change. Justice is absent behind these walls, which is evidenced from the lack of dignity and privacy afforded to us, our defective internal grievance system, the overuse of segregation, involuntary transfers based on allegations, and institutional charges.

Lack of Dignity and Privacy

Guards are extremely loud when completing their rounds through the living units, which is especially disruptive at night when prisoners are sleeping, where they also shine lights in our eyes. They also repeatedly wake up prisoners while we are napping during the day. It is rare that a guard treats us with respect or dignity. They demean us, lie, make accusations and assumptions, tease us, restrict our choices, belittle us, swear and call us names. For example, guards have made fun of what clothing women wear, our make-up, our weight and how much junk food we purchase at canteen.

The guards conduct searches of each unit at least once a month and can search once a week or more if the institution deems it necessary. Guards read and seize our personal journals, notes, address books, and schoolwork during searches. They throw our belongings around our living spaces and destroy personal property without any repercussions. It is possible to file a claim for broken possessions. However, the warden approves or denies claims within the institution. Thus, they are often denied. After a search, it can take hours to clean our living unit.

Defective Internal Grievance System

When a woman puts forth a complaint, it goes to the correctional manager. A first level grievance is sent to the Warden or Assistant Warden. At this point, the warden can either grant your grievance or deny it. Often, first level grievances are denied for unclear reasons. Only a second level (highest level) grievance goes to National or the Commissioner of CSC. The entire process is internal, as CSC staff make all decisions on whether the grievance is approved. Therefore, no one is watching the watchers or holding CSC accountable. This process allows CSC to abuse their power. Many women feel powerless and fearful of fighting for their rights. They distrust the system and experience significant amounts of stress.

We believe an external independent group1 should be created to deal with prisoners’ grievances. Allowing CSC to ‘investigate’ itself is an inherent injustice and lacks transparency. Additionally, prisoners’ grievances should be handled fairly and efficiently, within three months of being filed, not three years, as is often the case.

Overuse of Segregation

CSC regularly places prisoners in segregation for over 15 days, including those who are living with or experiencing mental health issues. Despite the deaths of two young women in segregation at Grand Valley Institution in less than a decade (Ashley Smith in 2007 and Terri Baker in 2016), management continues to place women with histories of mental health issues and self-harming behaviours in segregation. Both writers have spent time in segregation at GVI, and one author was in the segregation unit for 32 days just 3 months after Miss Baker’s death, for a minor, non-violent offence. Anytime a woman self-harms, no matter the severity, she is placed in segregation. The conditions in the segregation unit are deplorable. Being placed in segregation results in a deteriorating attitude, feelings of isolation, alienation, loss of identity, increased mental health issues, and feeling oppressed and disconnected from the community.

Involuntary Transfers and Allegations

We denounce the transfer of prisoners based on unproven allegations. Security intelligence files are created based on ‘reliable sources’ consisting of information from other prisoners given to CSC staff in secrecy. We are never allowed to know who or what was said exactly or able to confront our accuser in a transparent process. Other prisoners provide information, often false, for personal gain and favour from staff. This information can impact our security rating and parole hearings, restrict our access to visits with family and friends, limit community access, and eliminate our employment positions. If our security levels are increased we can be transferred from the minimum unit to the medium compound or from medium to the secure unit. Once a prisoner is transferred, it can take months or even years to return to a lower level setting. This requires women to start all over again, resulting in a loss of community and having to rebuild relationships. Women feel powerless, hopeless and anxious in such circumstances.

Institutional Charges

In minor court, a Correctional Manager (CM) rather than an outside adjudicator facilitates the process. The CM will universally find us guilty regardless of facts. This charge will follow the women through their entire sentence and be mentioned in all of their paperwork under institutional adjustment and behaviour. These areas are the domains that are looked at for your security rating scale, which makes you a minimum-, medium- or maximum-security prisoner. Your scale can restrict you from earning a transfer to minimum-security. Additionally, this charge could potentially pose a concern to the police and halfway house when transitioning into the community post-release.

2 - Employment Issues

The most salient employment issues within prison today include a lack of job opportunities and wage cuts. Employment is an integral aspect of prisoners’ correctional plans and central to our future success in the community after our time inside comes to an end.

Lack of Job Opportunities in Prison

Our security classification restricts our ability to apply for certain jobs. Women in maximum-security can only hold one job. At the minimum-security unit (MSU) there are no full-time jobs. However, women in minimum-security can apply for temporary absence work release programs to access employment in the community. These jobs are often limited due to lack of placements and difficulty to maintain them. If there are any issues within the prison, such as a lockdown, we are not able to leave the prison for work.

The “position of trust” clause restricts many women from finding, keeping and maintaining a job. Virtually every job, except for a few cleaning jobs depending on their location (for example, in the gym, bathroom or hallway) are all positions of trust. We lose our job if we get a major charge. Certain jobs, including canteen operator, can be lost with a minor charge, which includes innocuous activities like passing food or borrowing clothing.

The new Drug Strategy, which emanates out of the Roadmap to Strengthening Public Safety (Sampson et al., 2007) can prevent us from working for three months at a time or up to six months or more.3 Women can easily lose their job if they receive an institutional charge or are placed in segregation without being charged, even when the charge or the situation is completely unrelated to their employment. The lack of job opportunities in prison means we have little opportunity for skill development and limited financial resources to keep in contact with our family or prepare for our eventual release.

Wage Cuts and “Double Dipping” Taxes

The Government of Canada convened a parliamentary committee in 1981 to determine what prisoners’ wages should be based on the minimum-wage at the time, while also taking into account the cost of room and board. They determined our daily wage for full-time work should be $5.80 per day. The maximum daily wage rose some years later to $6.90. Then, in November 2013, the federal government implemented a policy to take an additional 30%4 off our wages for “food and Accommodation” (22%), as well as the administration of the “inmate telephone system” (8%) essentially causing us to pay this fee twice. At full-time pay we only take home $29 every two weeks. Our wages have not been reviewed in over three decades, despite the increased cost of living. Women use this money for hygiene, snacks and contact with family (e.g. phone calls and letters).

We should have access to real wages, not pennies. CORCAN (Corrections Canada Industries) is an entity within CSC whose mission is to provide meaningful employment and skills. It once provided additional opportunities in the form of incentive pay5 that allowed long-term prisoners to keep their families together and short-term prisoners to save money for release. All bonuses and incentives were cut in 2013. Our pay rate should be equal to the provincial minimum wage.

3 - Programs and Education

Concerning programs and education, for the federally sentenced women we spoke to the central issues pertain to the mother-child program and unnecessary bureaucratic control over volunteer-led programs. Additionally, there is a lack of access to computers and the library, and limited access to trades and post-secondary education programs.

Mother-Child Program

The mother-child program was one of the many programs that was substantially overhauled during the Conservative government’s reign from 2006-2015. In its previous iteration, the program enabled women to live with their young children, ages five and under in a cottage designated as the mother-child unit located on the general compound. Due to its location, there were no delays for a pregnant woman between the time she gave birth and when she was able to live with her child. A prisoner who was pregnant would work with a social worker and her case-management team at GVI in order to live in the mother-child unit, and following the birth of her child would be able to return to the unit with her newborn.

This program was shut down for years and has only recently been reinstated at the minimum-security unit (MSU) approximately one year ago in spring 2016. The current mother-child program is only a shadow of what it once was.6 There is one mother-child floor at the MSU, which is an apartment-style complex. There is only space for four women and their children to participate in the program at any one time. There are many bureaucratic constraints and extraneous processes so it can take eight to twelve months or even longer for a woman’s child to be able to move in. Aside from the required paperwork, a woman also has to earn her minimum-security rating and finish all necessary programming prior to moving to the MSU. This results in her not seeing her child outside of visits for twelve months or more. The visiting room is not a conducive location for a mother to bond with her child. Aside from the guards, search dogs and overall institutional atmosphere, women have been denied the opportunity to hold their baby, breast feed and change diapers. The guards often make allegations that prevent women from participating in the mother-child program. For example, below is a recent story from a young woman who was pregnant and gave birth while incarcerated at GVI. She has been striving to participate in the mother-child program and move to the MSU since she learned she was pregnant.

Kendall's Story7

When Kendall gave birth to her son this year, two female guards, who were present at all times, escorted her to the hospital. The child’s father, Kendall’s boyfriend, was not allowed to be present in the room while she was in labour. Once her child was born, he was immediately brought to the Natal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) due to breathing difficulties. Kendall was not initially allowed down to the NICU to see her son because the guards were unclear whether she had to be accompanied by a social worker or not. Kendall was forced to wait until the following day when a hospital staff member was able to contact the CSC social worker so that Kendall could spend time with her newborn son.

This was clearly devastating for Kendall, who wanted nothing more than to hold and establish a bond with her newborn child. Kendall has been a model prisoner since arriving at Grand Valley in 2016. She has completed all required programming, attends school, is employed within the institution and works closely with her case management teams. Her goal is to earn her minimum- security rating so she can move to the MSU and live with her son. Kendall is serving a three-year sentence. After almost one year she should not only be deemed a minimum-security prisoner, but she should also be eligible for day-parole, if not full-parole. The Children’s Aid Society (CAS) is supportive of Kendall having her son live with her at GVI, but the institution keeps making allegations that she is engaged in illicit activities, without having any evidence to substantiate their claims. The prison has intercepted her phone calls for two months, conducted random urinalyses (all of which came back negative), and requested a strip search (which she consented to) in order to determine whether she has received any new tattoos while incarcerated. Each of these situations have resulted in delaying Kendall’s security-level review, causing a lengthier wait for her to spend time bonding with her son at this critical point in his life.

Being disconnected from one’s children can negatively influence a mother’s relationship with her child indefinitely. Women separated from their children feel isolated and alone, which leads to feelings of anxiety, frustration, anger, and low self-esteem. We recommend the full reinstatement of the mother-child program as it was prior to the Conservative government coming into power, for women in the medium- and minimum-security level areas of the prison.

Bureaucratic Control over Volunteer Lead Programs

The institution practices unnecessary bureaucratic control over positive education and social programs. Since the Walls-to-Bridges (W2B) program began in 2011, the prison is increasingly using their power to control the initiative. Students now have to submit papers to institutional teachers prior to submitting them to the outside professor. The inside teacher and outside professor must now report to the prison if anything in a student’s paper can be deemed “too radical”. Teaching assistants, who are hired by professors from an outside university, can be fired by the institution after receiving an institutional charge.

Volunteers from the community lead other programs such as Celebrate Recovery, Alternatives to Violence, and Stride, often having to jump through various bureaucratic hoops in order to enter the prison, bring snacks or supplies, and take us on temporary absences. These volunteers have been attending the prison for years and are generally well-known by CSC staff, yet are sometimes treated with suspicion and disrespect. Staff have threatened to cancel full-day programs that occurred over countless times simply because a few prisoners had to use the washroom during the ‘lockdown’ time.

As soon as an activity is legitimized as a program (i.e. a formally structured activity approved by institution), it has the potential to be shut down by management. At GVI, we had an active music program that was available to women during the afternoons when we had no other work or required programming scheduled. The music program had been operating informally for one year with the approval and support of a Social Program Officer (SPO). The music program involved an instrument-lending program, vocal lessons, song-writing workshops and lessons for various instruments (e.g. guitar, keyboard, bass guitar and drums). Within one month of the SPO staff retiring, who had supported the program, middle management shut us down. Apparently, certain guards do not like the fact that women are able to attend this program during the day.

Lack of Access to Computers and Library

It is extremely difficult for women to access computers. Teachers and other CSC staff control access to the rooms that contain computers and often will not allow us to enter the room. Access to personal computers in our living units should be reinstated. The library is only open Tuesday, Wednesday and Thursday. Women can only access the library from 10:00am to 10:30am and 2:00pm to 2:30pm, as well as during their living unit day and hour. Sometimes the library is closed on these days if the librarian is absent. The library should get more up-to-date educational books, and be open during evenings and weekends. It is extremely difficult for women to study and do our schoolwork. This leads to feelings of frustration, anger, hopelessness and powerlessness.

Lack of Access to Trades and Training Post-Secondary Education

Over the past twenty years, CSC has cut off our access to almost all trades programs and eliminated access to post-secondary education in the community. Women at GVI are currently working on an amendment to the CCRA for an education release, which is similar to a work release. GVI has extremely outdated computer hardware without any access to the internet. Not having the internet available for educational purposes inhibits our ability to access many high-school and post-secondary courses since print-based courses are no longer available.

We should have access to post-secondary education so that we can pursue academic degrees while incarcerated. We should have access to education about technology. Progressive changes to technology in the community leave us struggling to function upon our release. We should have access to the internet that is monitored and restricted. Many software programs are available to facilitate this process. The high school program is mostly self-directed independent adult learning, but students must sit in classroom to “prove” they are working, even if they are diligent and hardworking, while other students are disruptive. Students with lack of education, learning disabilities or mental health diagnoses are held to a lower standard and given their high-school credits without doing much work, while at the same time not provided with a tutor or support to understand the concepts being taught. For example, a woman in grade 11 English cannot write a grammatically correct paragraph without a spelling error and is being assigned books such as The Little Engine That Could. Students can receive a suspension from school for 90 days for simply falling behind or missing days.

We recommend the reinstatement of all social programs closed during the Conservative reign, including Lifeline, Prison Farm programs and life skills programming. There should be a reduction in wait times for access to programming. The elimination of access to education and social programs should no longer be used as a punishment. The high school program should be evaluated, improved and updated. Prisoners with high school degrees should be hired to work as tutors in the secondary school program. Many women would benefit significantly from the individual support.

4 - Food and Nutrition

Food and nutrition affects our overall health and wellbeing. National regulations and the high cost of food make it difficult to eat healthy. A lack of training for food safety and knowledge concerning how to prepare healthy meals are other common issues that women in prison face.

National Regulations and High Cost of Food

In the medium- and minimum-security areas of the prison, we cook our own food and receive $35.21 each per week to purchase our groceries. This amount has decreased within the past two years from $35.35 and the overall budget of approximately $35/week has not increased in the past 20 years since this GVI opened, despite inflation and rising food prices. Produce, dairy and meat are expensive, while processed, unhealthy items are cheaper and more affordable to eat.

CSC National Headquarters has recently regulated our menu in order to make it consistent with other institutions across Canada. Healthy menu items were removed and replaced with canned goods and processed, unhealthy food. For example, the maximum-security unit at GVI previously received 1% milk and now they get powdered milk every day.

By standardizing what we eat for every penitentiary across the country, we have less variety and choice, resulting in less cultural expression from each region of the country and cultural groups within each region. Many women enjoy cooking and baking, which is a positive, pro-social activity. Restricting our choices makes us feel worthless and inferior. The unhealthy food negatively affects our physical health.

Lack of Training for Food Safety and Preparing Healthy Meals

Some women have never cooked before. They do not know how to prepare a meal, create a meal plan or budget. Within the living units, several serious fires have occurred causing thousands of dollars in damage. At least five fires have occurred in the past four years due to inexperience and lack of knowledge or awareness of how to cook with oil or handle a grease fire. This lack of training and knowledge is not only unsanitary, but can also lead to the spread of infectious disease, bacteria and pathogens.

5 - Visits and Correspondence

The most common issues within the area of visits and correspondence include the disrespectful and suspicious treatment of our family and friends, the loss of visits as a punishment, a reduced number of family socials each year, as well as the loss of the annual Pow-Wow. Additionally, there are problems with our mail and phone systems.

Disrespectful, Suspicious Treatment of our Family and Friends

Ion scanner machines are designed to be able to detect trace amounts of particles, such as drugs, on clothes, money, jewellery, keys and other personal items. CSC has placed these devices in the lobbies and mailrooms of penitentiaries in an attempt to reduce the flow of drugs into the institution. False positives or very faint amounts can prevent visitor access. These devices are extremely sensitive and can pick up trace amounts of particles in the air. Once a visitor tests positive for a substance, the guards conduct a ‘risk-assessment’ to determine whether the visitor can enter the institution. Often, visits are suspended for a set period of time or indefinitely. Sometimes visits are closed (i.e. in a secure ‘box’ where the prisoner and visitor are separated by glass). Even if the visitor is allowed into the prison, the incident is noted on the prisoner’s file and follows us throughout our sentence. Visits can also be suspended or closed due to allegations from ‘reliable sources’ or prisoner informants with no substantial evidence. Additionally, without notice, guards suddenly cancel visits or deny family members from seeing prisoners, even when they have travelled for hours from out of town. Guards and search dogs are intimidating to our visitors. The guards in the visiting area tell our visitors where they can sit. Additionally, guards intervene if visitors stretch or visitors and prisoners sit too close, hold hands, hug, or touch for more than three seconds.

Loss of Visits as a Punishment

Family Day or socials are an opportunity for women to visit with family and friends for up to six hours in an informal atmosphere with music, food, games, and entertainment. Socials occur much less frequently than in the past. For several years now, there have only been two socials per year at GVI. Prisoners without family attending are no longer permitted to participate in the event, despite paying fees to their respective prisoner welfare committees all year to fund the event. Prisoners charged with a minor or major offence within the institution, within three months of the event are not able to attend. One of the authors was notified just 12 hours prior to the start of the event that she was unable to attend, without any charges being laid. This causes significant inconvenience to our families who have taken time off work or drive long distances and stay a local hotel to visit. The volume and rate of charges drastically increase months before Family Day. Because of these sanctions, less and less people have been attending each year.

We recommend the reinstatement of regular Family Day socials, at least six per year. We believe that every prisoner should be able to attend family day regardless of whether she has guests attending. We build relationships with one another and with each other’s social networks, and the socials are an opportunity to strengthen those ties. We should not be banned from attending a social simply because we have received an institutional charge within three months of the event.

Annual Pow-Wow

Only identified Indigenous prisoners can invite guests to the annual Pow-Wow. As of this date, the annual Pow-Wow has been cancelled without reason and without any communication to prisoners.

Correspondence

As one of our only means of accessing the outside world, regular postage mail is extremely important to us and can brighten a prisoner’s day. According to CSC policy, we are entitled to our mail every business day. CSC is supposed to deliver prisoners’ mail in the same manner that Canada Post does. However, we receive our mail infrequently as it is treated like a privilege. Some days we do not receive our mail at all and it can take weeks to receive local correspondence.

Phone System in Disrepair

There is one phone in the segregation unit. Over a one-month period the phone was broken five afternoons. In recent months, three living units experienced a period in which their phone was unavailable for days or even weeks. After every power outage, the telephone in several living units goes down for a period of time until it is fixed by Technical Support. The phone card uploads only occur once a month and the money has to be in your account one week prior. If a woman arrives at GVI around the date of the upload, the money has to be in their account and they have to wait an entire month to make any calls. These women are unable to contact their family and let them know how they are doing, and unable to arrange to have their boxes of personal belongings sent, which must arrive within 30 days of intake. Women are not able to contact any family or support persons who reside overseas. For example, a woman was unable to add a phone number in Europe to speak with her children and another woman was unable to call her mother overseas.

For long-distance calls, the rate is $0.11 per minute. For local calls, the rate is $0.56 per hour. The phone system is very sensitive and calls are often disconnected due to a “three-way call alert”, which can be triggered by background noise or a portable phone. Maintaining strong family ties and connections to our community through visits, correspondence, and phone calls are vital to the rehabilitation and reintegration process that CSC claims it supports. However, the damage caused by this flawed system is counter-productive. Furthermore, our family and friends are being punished by being disconnected from us and having to contribute to the costs of maintaining what little connection we have. They too are doing time even though we are the ones behind bars.

The negative impacts of having these issues with our visits, correspondence and phone system are numerous. Contact and relationship building with family and friends are vital to community reintegration. Without these outside connections, we feel isolated, lonely, disconnected, hopeless, powerless, frustrated, anxious, angry and unsupported. We recommend that CSC fix the phone system so the phone does not cut-off anymore. In addition, when our calls are cut-off, we should be reimbursed for the cost.

6 - Reintegration and Parole

CSC, as per the CCRA, is mandated to assist with the rehabilitation of prisoners and our reintegration into the community. CSC is currently not fulfilling its reintegration mandate. Parolees are sent back to prison frequently for issues that could be handled and managed in the community. While prisoners are still serving their sentences, it is difficult to connect people to supports in the community.

More community groups should be allowed into the institution as volunteers to make connections, as well as build relationships that help us to reintegrate back into society. This would assist with a healthier transition for individuals leaving the institution and making connections to the community.

Community Access for Women Serving Life Sentence

Women serving life sentences must go before the Parole Board of Canada (PBC) when asking for any Escorted Temporary Absences (ETAs), Unescorted Temporary Absences (UTAs) and work releases. The current system makes it tedious and time consuming for women serving life sentences to work on their reintegration. We recommend that the warden regain the ability to grant permission for ETAs and UTAs, along with work release as opposed to the PBC.

Challenges on Parole

Upon release, women are expected to work while on parole. However, many places will not hire someone serving a federal sentence. Additionally, the PBC can place further stipulations restricting us from working anywhere that serves alcohol or involves financial transactions, such as retail establishments, restaurants, fast food, and call-centres.

Women on parole are required to attend programming once a week for two hours for about a minimum of twelve weeks. Additional programming or treatment may be recommended. We are also required to meet with our parole officer. This makes working during the day extremely difficult. There is little to no support at all for employment once released. Additionally, many women do not have any personal identification. Furthermore, there is limited assistance with transportation and housing. If women reside in a halfway house and work, we are required to pay rent, which makes saving up to move to our own apartment difficult.

Women are not able to collect government assistance (e.g. Ontario Works, Ontario Disability Support Program, etc.) at most halfway houses in Ontario. Therefore, a woman with a disability cannot receive her cheque even though a doctor has said she is unable to work. One of the main reasons women cite for reoffending is due to financial difficulties and being unable to secure employment.

There are not enough halfway houses for women in Ontario. Women are waiting weeks or even months to get a bed in southern Ontario, in cities such as Hamilton and Toronto. Currently, there are only seven halfway houses for women located in London, Hamilton, Toronto, Brampton, Barrie, Kingston and Ottawa. Many women are forced to live hours from their community when released on day-parole, especially those from northern Ontario. We are often forced to waive our full parole, which would allow us to go home, in favour of day-parole in a halfway house. Women should be able to return to their homes and families via parole after serving a third of their sentence, as outlined in the CCRA.8

Due to the many issues with reintegration and parole outlined above, women often feel unprepared, anxious, unsupported, and ultimately unable to function independently in the community. Women can also experience a lack of self-esteem, lack of confidence, lack of skills and be distrustful of the system.

We recommend alternatives to imprisonment for parole violations when the law is not broken. For example, a non-association clause requires parolees to assess people they just meet within the first 15 minutes to determine whether that person has a criminal record, an active police file or is engaged in any illegal activities. This can be an awkward or even dangerous conversation. The PBC should cease imposing this clause. Women have also been sent back to prison on a parole violation for being a few minutes late to an appointment. This is unjust.

7 - Media and Communications

Prisoners are discriminated against in the media. News articles and television shows focus on high profile cases and violent offences. Negative media attention increases unfounded fears. With a constant focus on the sensational, we face discrimination upon release into the community, especially with regards to employment. We recommend that rehabilitation and successful reintegration stories be celebrated in the media to demonstrate the hard work and dedication of prisoners and our families. Having an open-minded, understanding community is necessary to reduce harm, decrease recidivism and encourage successful reintegration. Community advisory councils, made up of volunteers that visit women inside the prison, can play an educative role in their local communities, so that we are seen as an integral and valuable member of the community once released. They can act as allies and advocates to break down stereotypes and prejudice.

Recently, the media has requested to speak with individuals regarding the death of a prisoner while she was in segregation. Terri Baker died in July 2016. As we mentioned above this was the second death of a young woman in segregation at GVI. The first death was Ashley Smith in October 2007. Both women lived with mental health issues. The prison did not approve any media requests for these matters. The media has also attempted many times to access prisoners to hear our stories (e.g. The Fifth Estate), but the administration and the staff blocked access. We have found creative means to get our stories out to the public, but if we are discovered, we are penalized. Media should be given access into all areas of the prison to speak with prisoners as a means of fostering government accountability.

8 - Focus on Punishment

The federal penitentiary system has become increasingly focused on punishment as opposed to rehabilitation. This can be seen in prisoners’ common mistreatment by guards, the restriction of our pro-social activities and the deployment of a drug-strategy used to punish, rather than offer treatment or support.

Mistreatment by Guards

The entire system from the top down practices paternalistic control over incarcerated women. We are treated like children who are unable to make independent choices. The policies and practices are designed to restrict and control, rather than rehabilitate and reintegrate. The focus of the institution is on punishment and security. Staff are generally insensitive. Guards mistreat us through verbal comments, a lack of understanding and compassion, and ignorant remarks. The LGBTQ community at GVI feel they are not accepted as individuals and especially not as a community. Gay relationships are prohibited and are not accepted by the guards. An individual’s partner is often mentioned in paperwork. Women in relationships have not been supported for parole due to their relationship and their partner of choice. Same-sex couples are also not permitted to have Private Family Visits together.

Restricting Pro-Social Activities

There is no lounge or common area outside of our living units that women can use for social activities, aside from the gymnasium. When the weather does not allow for outdoor gathering, women are forced to use the gym as a multipurpose room for eating, playing cards, doing crafts, playing music, playing sports and working out. The gym should be strictly for athletics. Guards restrict women from using the classrooms for social activities. We are not able to visit each other’s living units without risking a major charge. We recommend the creation of a lounge for women to socialize, play cards, share a meal or simply just have a conversation with another as human beings. We also believe that visiting between living units should be allowed each evening and every weekend so friends can watch television, listen to music, cook and eat together, and build relationships.

Drug Strategy

When the drug strategy is deployed, it has serious consequences, many of which impose restrictions that have nothing to do with drug use. The drug strategy can be implemented if a woman fails to provide a urinalysis within a two-hour period of it being requested, tests positive from a urinalysis, improperly stores her medication (i.e. has a prescribed medication out of the blister pack), is found with a sewing needle, is found with over-the-counter medicine that is not prescribed (e.g. Tylenol) or is the subject of allegations. CSC claims that the drug strategy assists women, helping them to avoid using substances and to keep drugs out of the prison, but neither of these objectives are met. Instead, the strategy is a punitive instrument comprised of many sanctions.

Some punishments of drug strategy include pay deductions, moving living units, losing one’s employment, and being unable to be a part of socials or activities in the prison. An individual is unable to work for the entire duration of their drug strategy term, which is usually 90 days, but the duration can be extended for up to six months or more, for whatever reason CSC deems necessary. An individual on the drug strategy is also not able to attend the Walls-to-Bridges education program or be the teaching assistant as it is a job within the institution. While on the drug strategy, an individual can be denied visits and is unable to have any Private Family Visits. Being placed on the drug strategy causes us to feel a loss of identity, because everything positive is taken from us. We also feel targeted, controlled, helpless, powerless, frustrated, labelled, stereotyped and isolated. Addiction should be recognized as a mental health issue requiring treatment, as opposed to a behavioural issue that requires punishment.

9 - Health and Dental Care

There is a lack of accessibility to proper medical services inside the prison. Many people wait years for a diagnosis, and then even longer for any necessary surgery. It can take weeks or months to see a doctor or dentist, even for antibiotics or a common cold or flu. The dentist at GVI specializes in extracting teeth and prefers pulling a tooth to providing a filling. There are no teeth cleaning or preventative care appointments available. CSC blocks most standards of care and prohibits many necessary medications from being prescribed. For example, simple non-narcotic nerve medications and standard muscle relaxers are not available, even on a direct observation provision from nurses. Instead, doctors prescribe various psychotropic and mood stabilizing medications instead of pain relievers. Holistic care is difficult, if not impossible to access. There is no access to a chiropractor or massage therapist, even if women are willing to pay for it themselves. It is challenging to get items such as wrist or knee braces.

Not having proper access to health care is dehumanizing and causes us to feel worthless and inferior, as if nobody cares. Preventable health conditions occur and current health problems worsen. This can lead to chronic pain, physical exhaustion, and depression or anxiety. Lack of access to proper dental care can lead to bleeding or inflamed gums, cavities, and teeth being pulled out. Preventative health services should be made more accessible. Female prisoners should have the same access to preventative health care, such as breast cancer screening and annual pap tests, as women in the community. CSC should honour prescriptions written for us by doctors outside the facility. Teeth cleanings and regular dental check-ups should be available for people.

10 - Mental Health Care

Many women are over-medicated with psychiatric drugs. Psychology only allows twelve sessions even if someone is in severe distress (e.g. has self-harmed or recently been released from serving more than fifteen days in segregation or maximum-security). The focus of CSC Psychology is on women with serious diagnosed mental health issues (e.g. schizophrenia, bipolar, borderline personality disorder). Counselling sessions are supposed to be confidential, unless we are a risk to ourselves or others, or are jeopardizing the security of the institution. However, since psychologists are employed CSC staff, women do not feel comfortable sharing their feelings and struggles based on the fear that what they say will end up in their paperwork. Their case management team could be notified of anything they say, which would affect security ratings, temporary absences and parole. If a woman expresses that she may hurt herself she is quickly placed in segregation, stripped of her clothing, placed in a canvas “baby-doll dress” and strapped to a table until the institution believes she is able to keep herself safe. GVI does not have the capacity to care for women with severe mental health issues. The lack of appropriate mental health care leads to verbal and physical altercations in living units, women feeling misunderstood, exacerbated mental health issues, distrust, self-harm, and even death. We recommend that CSC return to hiring external social workers on contract to work with women in distress and those living with mental health issues, rather than CSC-employed psychologists.

Conclusion

Throughout this essay, we identified ten priorities for change based on our own experiences of incarceration. These key themes include: justice, employment issues, programs and education, food and nutrition, visits and correspondence, reintegration and parole, media and communications, a focus on punishment, health and dental care, and mental health care. Within each category, we elaborated on the problems we have observed and/or experienced, discussed the impacts these issues have on incarcerated women, and suggested some recommendations for change.

There are numerous impacts of the previous Conservative government’s punitive agenda, which shaped criminal justice laws, policies and practices. This in turn resulted in many negative impacts on federally sentenced women. The most common issues that affect us due to the punitive prison environment include low self-esteem, stress, anxiety, fear, feeling disconnected from one’s community, a sense of hopelessness, helplessness, worthlessness, isolation, alienation, frustration, oppression, inferiority, loneliness, distrust, feeling dehumanized, intimidated, and unable to function independently in the community. These negative impacts affect women emotionally, psychologically, physically, socially and spiritually.

Our overall recommendation is that CSC revisit and implement the recommendations outlined in Creating Choices: The Report of the Task Force on Federally Sentenced Women from 1990. This document was built on principles of empowerment, meaningful and responsible choices, respect and dignity, and a supportive environment. The six federal regional facilities for women across Canada were intended to be created, developed, and built on the principles and recommendations in the Creating Choices document. While their implementation was imperfect, the vision has been sidelined since 2006, when the Conservatives were elected to form a minority government. Creating Choices is a comprehensive study, which covers the issues we discussed in this paper.

ENDNOTES

It should be recognized that the Office of the Correctional Investigator (OCI) is mandated to provide independent oversight of CSC. However, the CSC internal grievance process is self-regulated. Unlike the OCI whose powers extend only as far as making recommendations to CSC, the authority of those who respond to grievances is final. At the first level of the grievance process the authority is granted to the warden or manager in charge of the department being grieved and at the second level the authority is CSC’s Commissioner.

2Interestingly, the Liberal government’s latest act to amend the CCRA includes the following: “The Bill proposes to reinstate the CCRA guiding principle “least restrictive measures” in Part I of the Act. For consistency, the guiding principle of “least restrictive determination” would be reinstated to deal with conditional release in Part II of the Act” (Canada, 2017).

3According to Commissioners Directive 730 Offender Program Assignments and Inmate Payments, in effect 2016-08-22, paragraph 38: “The inmate’s program/work supervisor will complete an assessment of the inmate’s participation in the program assignment using the Inmate Performance Evaluation form (CSC/SCC 1138) at least once every six months, and any time the program assignment ends” (Correctional Service Canada, 2017a).

4As stated in Commissioners Directive 860 Offenders Money, section 6: “Inmates at pay level D to pay level A, as defined in CD 730 – Inmate Program Assignment and Payments, will normally contribute 22% of their CSC payment toward the cost of food and accommodation” and paragraph 16: “Inmates at pay level D to pay level A, as well as at the two allowance levels, as defined in CD 730 – Inmate Program Assignment and Payments, will normally contribute 8% of their CSC payment toward the cost of the administration of the inmate telephone system” (Correctional Service Canada, 2017b).

5According to a Toronto Star op-ed: “Prisoners who work for the profitable CORCAN program, producing products and services for government and private sector contracts in the areas of manufacturing, construction, textiles and other services such as laundry, earn an additional hourly “incentive” pay that is approximately $1.25 to $2.50 per hour on top of the flat daily rate” (Devellis, 2012).

6According to Commissioners Directive 768 Institutional Mother Child Program in effect 2016-04-18 (Correctional Service Canada, 2017c) substantial changes to that directive were made which restricted access to the program, specifically the following: “The eligibility criteria, documentation requirements and procedures for the residential program have been modified as it relates to inmate participants, babysitters and inmates residing in a housing unit where children reside on a full-time or part-time basis and “The child’s upper age limit for the part-time residential program in the living units has been lowered (from 12 to 6 years of age)” (Correctional Service Canada, 2017d).

7Kendall is a pseudonym used to protect the anonymity of the woman who shared her story with us.

REFERENCES

Correctional Service Canada (2017a) Commissioners Directive 730 Offender Program Assignments and Inmate Payments, Ottawa. Retrieved from http://www.csc-scc.gc.ca/acts-and-regulations/730-cd-eng.shtml

Correctional Service Canada (2017b) Commissioners Directive 860 Offenders Money, Ottawa. Retrieved from http://www.csc-scc.gc.ca/lois-et-reglements/860-cd-eng.shtml

Correctional Service Canada (2017c) Commissioners Directive 768 Institutional Mother Child Program, Ottawa. Retrieved from http://www.csc-scc.gc.ca/politiques-et-lois/768-cd-eng.shtml

Correctional Service Canada (2017d) Policy Bulletin 531, Ottawa. Retrieved from http://www.csc-scc.gc.ca/politiques-et-lois/531-pb-eng.shtml

Correctional Service Canada (2017e) Commissioners Directive 712-1 Pre-Release Decision Making, Ottawa. Retrieved from http://www.csc-scc.gc.ca/politiques-et-lois/712-1-cd-eng.shtml

Correctional Service Canada (1990)Creating Choices: The Report of the Task Force on Federally Sentenced Women, Ottawa.

Devellis, Leah (2012) “Plan to cut inmates’ pay will accomplish nothing”,Toronto Star – May 14.Retrieved from https://www.thestar.com/opinion/editorialopinion/2012/05/14/plan_to_cut_inmates_pay_will_accomplish_nothing.html

Office of the Correctional Investigator. (2015) Annual report of the Office of the Correctional Investigator 2014-2015,Ottawa.

Public Safety Canada (2017, June 19) An Act to amend the Corrections and Conditional Release Act (CCRA) and the Abolition of Early Parole Act (AEPA). Retrieved from https://www.canada.ca/en/public-safety-canada/news/2017/06/an_act_to_amend_thecorrectionsandconditionalreleaseactccraandthe.html?=undefined&wbdisable=true

Sampson, Robert, Serge Glascon, Ian Glen, Clarence Louis, and Sharon Rosenfeldt (2007) A Roadmap to Strengthening Public Safety, Ottawa: Minister of Public Works and Government Services.

Published courtesy of JPP 26-1-2_2016

The Journal of Prisoners on Prisons (JPP) is an academic and peer-reviewed journal published by the University of Ottawa Press that features articles written by current and former prisoners. Learn more about the JPP at www.jpp.org or send inquiries to jpp@uottawa.ca.

Comments

There are 0 comments on this post